¶ Description

Correct Spelling-Mistakes in text fields.

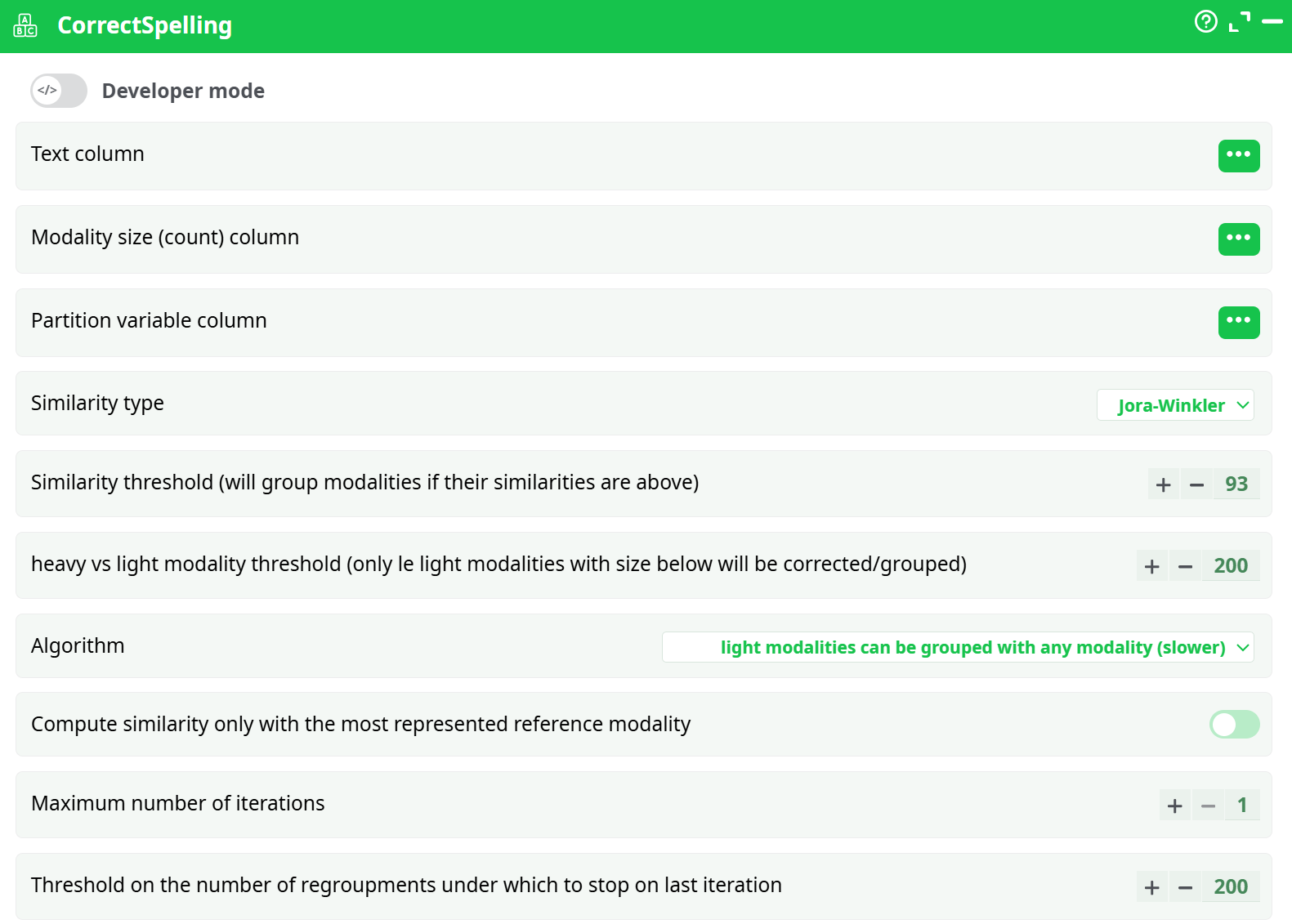

¶ Parameters

Parameters:

- Text column

- Modality size (count) column

- Partition variable column

- Similarity type

- Similarity threshold

- Heavy vs light modality threshold

- Algorithm

- Compute similarity only with the most represented reference modality

- Maximum number of iterations

- Threshold on the number of regroupments under which to stop on last iteration

¶ About

ETL include an operator that checks & corrects the spelling mistakes in any text field. For example, let’s assume that your database contains a field named “City of Birth”. This field will usually contains many different orthography (i.e. spelling error) of the same city. The CorrectSpelling action will detect and correct these errors automatically. It’s typically used to “clean” the database to get better reports, better predictive models, etc.

NOTE :

For example, the city "RIO DE JANEIRO" can be mis-spelled in a number of different ways (this is a real-world example):RIO DXE JANEIRO, RIO DE JAEIRO, RIOP DE JANEIRO, RIO NDE JANEIRO, RIO DEJANEIRO, RIO DE JANEIRO, RIO DE JANIRO, RIO DE JANEI RO, RIO DE JANEIRIO, RI0 DE JANEIRO, RIO DE JNEIRO, RIO DE JANEEIRO, RIO DE JANEIROO, RIO DE JANAEIRO, RIO DE JANEIROR, RIO DE JANEIRO RJ

This action can operate in two different modes:

- You don’t have any reference table.

- You have a reference table (For example, you have a table that contains the exact orthography of all the possible city names).

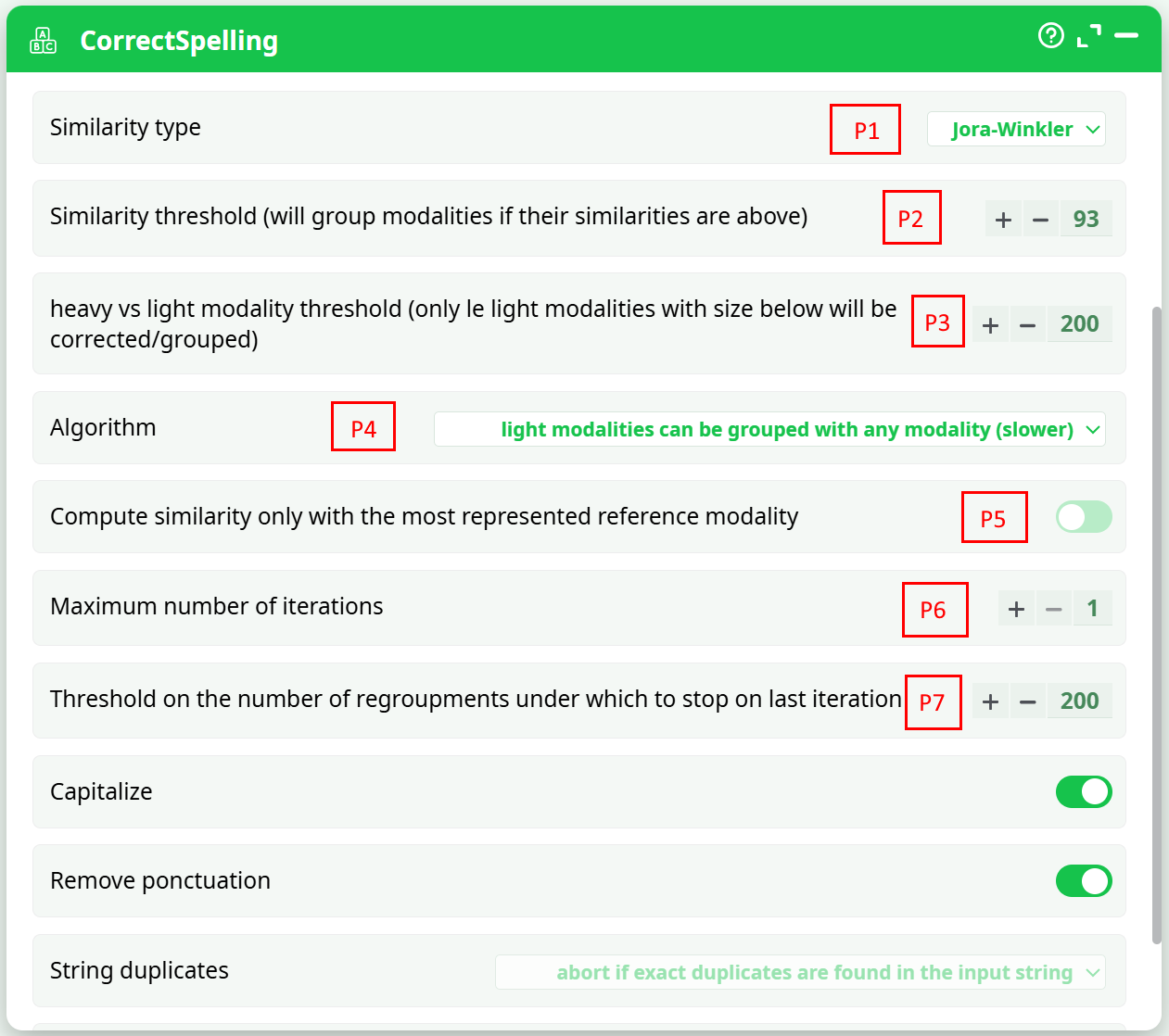

Here are the parameters of this action:

¶ Mode 1: No reference Table

Let’s go back the “city name” example: i.e. We have a table with different city names, some of them have some spelling mistakes and we want to correct these mistakes.

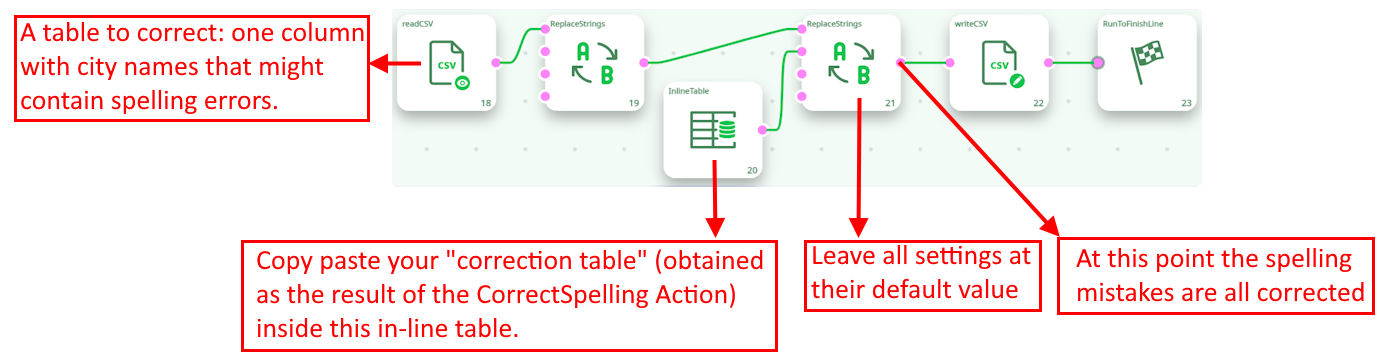

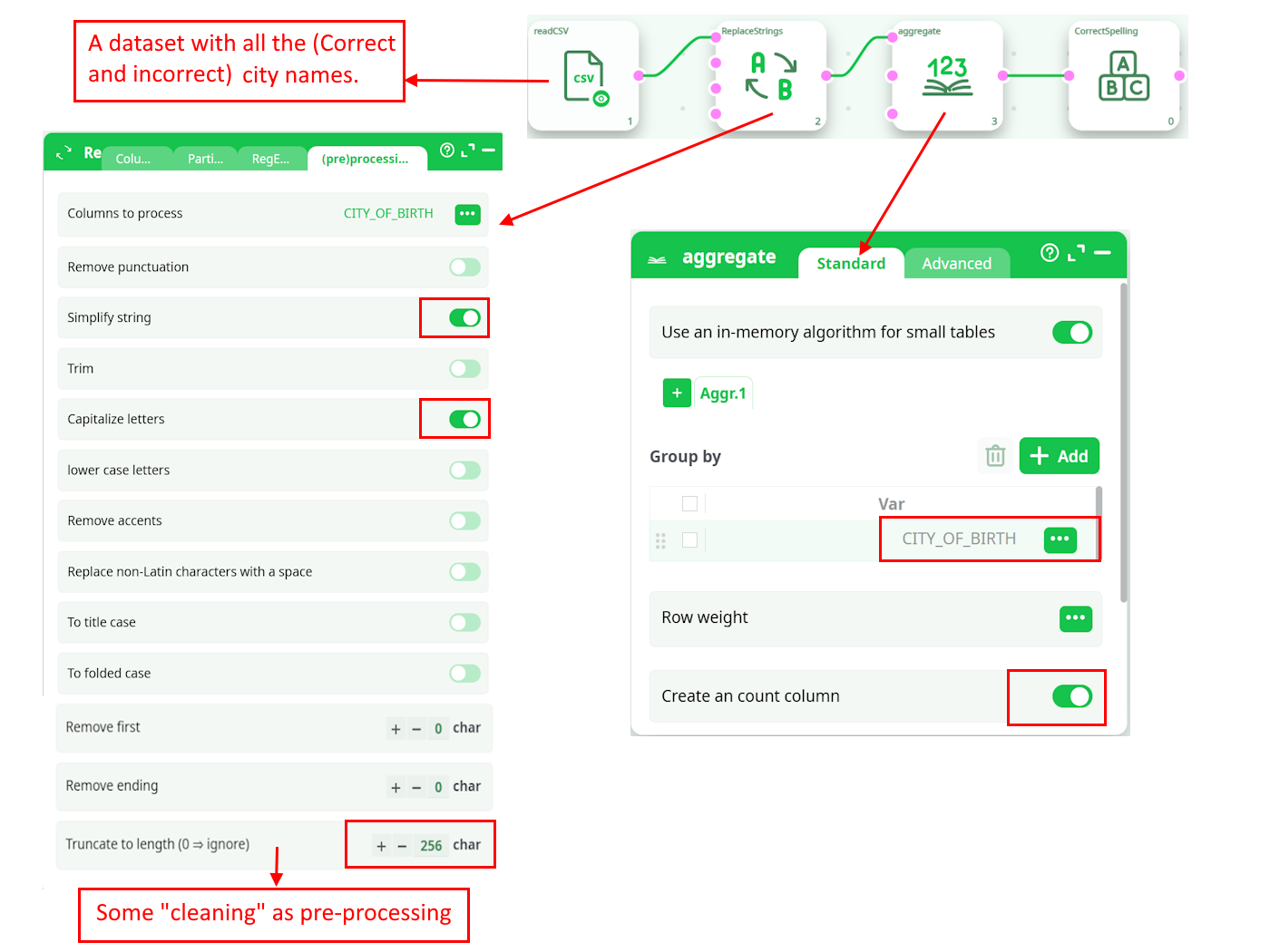

We’ll typically have such a pipeline:

Some modalities practically never appears inside the text corpus. These very “Light” strings (in opposition to the “heavy” strings) could easily be spelling errors. The threshold between a “Light” and a “Heavy” modality is given in parameter P3.

A given string is a spelling error (that must be corrected) if:

- It’s a “Light” modality.

- It’s “very similar” to (i.e. it “looks like”) another string X. Depending on the parameter P4, the other string X can either be:

- A “heavy” string (This is, by far, the fastest option: Use this option if you have performance issue and the running-time is too long).

- Any string slightly heavier than the string currently being “corrected”.

The parameters P1 and P2 defines if two strings must be declared “very similar”.

What’s happening with the cities that have a small population in real-life? All these cities will only have a small representation inside the database (i.e. they will never be classified as “heavy” modalities). To still be able to correct the spelling mistakes of these “small cities”, you must set the parameter P4 to the value “regroup with any other modality” (this is actually the best choice, but it’s much slower).

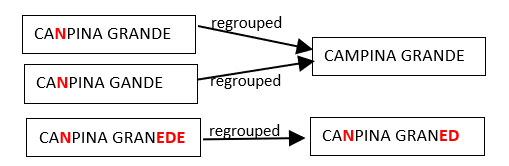

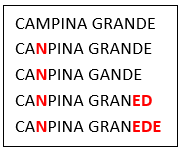

All the strings that are spelling errors are “regrouped” with the string that is the most likely to have the correct spelling (i.e. with the most represented string). So, we can have the following re-groupings:

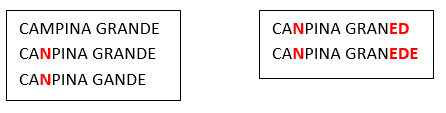

Hereabove, we see that many people make the same spelling mistake: i.e. They replace the “M” letter with the “N” letter inside the word “CAMPINA”. Let’s now assume that, after the corrections/regrouping illustrated above, we find the following two new “groups”:

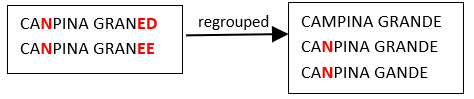

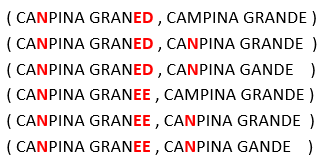

We see that, amongst the many people that erroneously write CANPINA (instead of the correct orthography “CAMPINA”), there are some people that don’t manage to write correctly the word “GRANDE” neither (i.e. they erroneously write “GRANED” or “GRANEDE” instead). The two groups illustrated above are quite similar because CAMPINA is written with exactly the same spelling mistake (“CANPINA”) in both groups. Thus, it would be nice if these 2 groups would new be merged together in a second iteration (because they most likely represent the same city “CAMPINA GRANDE”):

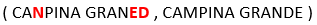

Such that we finally obtain one final group:

Note that these 5 strings could not be “regouped” together at the first iteration (for example, because “CANPINA GRANED” is “too far away” from “CAMPINA GRANDE”) …But the group containing “CANPINA GRANED” is similar enough to the group containing “CAMPINA GRANDE”, so that it’s still possible to regroup these 2 groups in a later iteration.

We can now give more details about the spelling-correction-algorithm used in ETL. The algorithm is:

- Assign all initial strings into different groups (one string per group).

- Consider all the “Light Groups” (i.e: the “Light Groups” are defined by “the sum of the occurrence of all the string’s weight inside a “Light Group” is below the threshold given in parameter P3”) in the order from the “lightest” to the “heaviest”: A given group can be merged with another group X if it’s “very similar” to this other group X.

The candidate groups X are selected based on the value of parameter P4. Depending on the parameter P5, the similarity between two groups is …:- P5 is not checked: … the average similarity between all the string-pairs. This means that, in the above example, the similarity between our two groups is the average of the similarity between the following string-pairs:

- P5 is not checked: … the average similarity between all the string-pairs. This means that, in the above example, the similarity between our two groups is the average of the similarity between the following string-pairs:

This is the best option, although it’s very slow.

- P5 is checked: … the similarity between the most represented string in each group.

This means that, in the above example, the similarity between our two groups is the similarity between the following 2 strings:

- Decide if another iteration is required: If yes, go back to step 2.

The parameters P6 and P7 are used to decide how many iterations the algorithm does. Most of the time, one iteration is enough. Some time, two iterations can be useful (but the second iteration usually takes a huge amount of time).

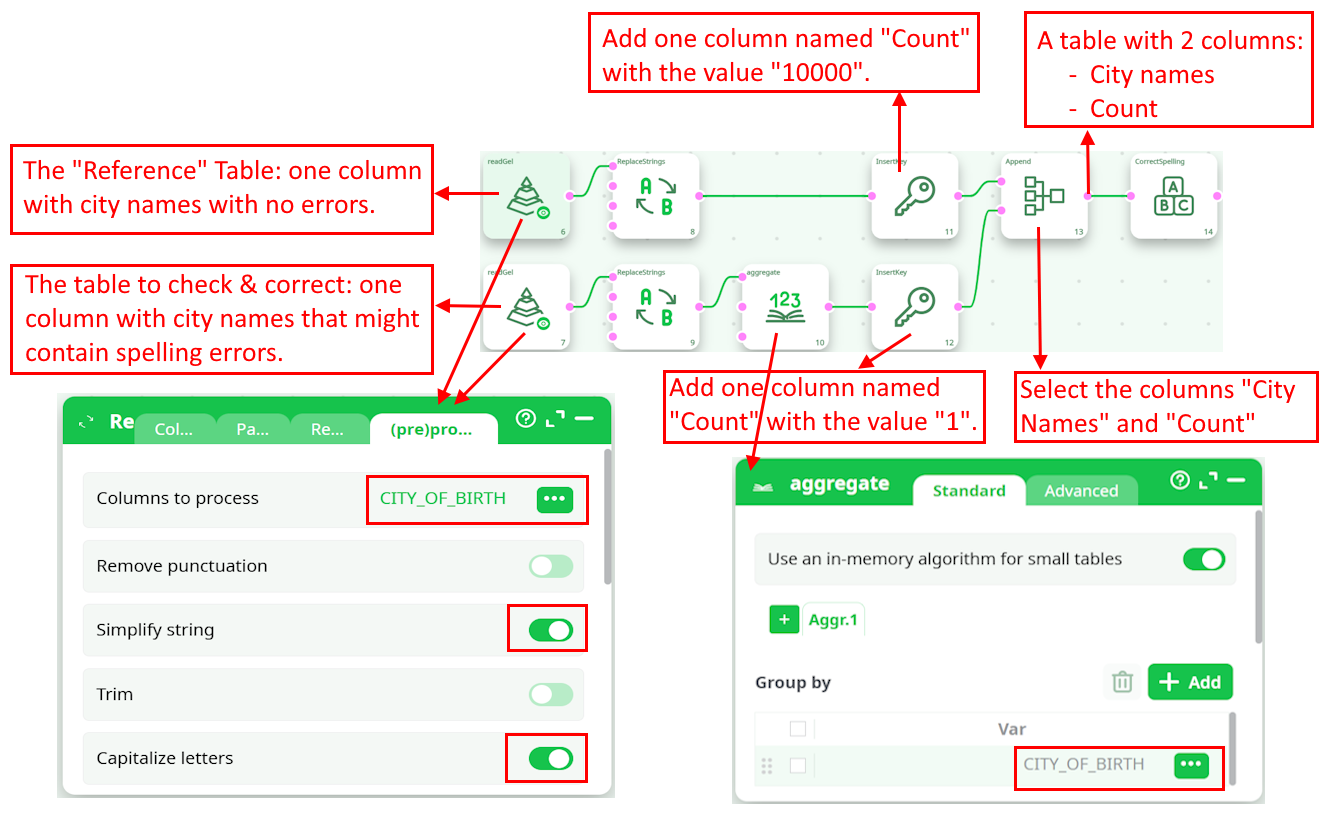

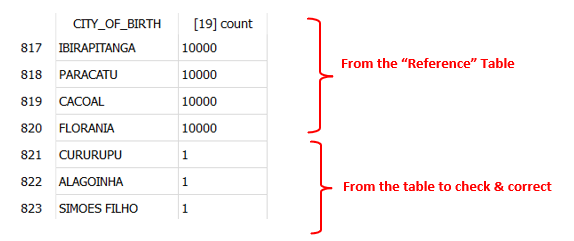

¶ Mode 2: We have a reference Table

Let’s go back the “city name” example: i.e. We now have two tables that contains city names:

- The first table contains no errors inside the city names: This is the reference table.

- The second table contains city names that might have some spelling mistakes and we want to correct these mistakes.

We’ll typically have such a pipeline:

As input to the CorrectSpelling action, we have such a table:

All the cities from the reference table have a “heavy weight” (greater than the parameter P3) such that no attempt to “correct” them will be made.

When using a reference table, the parameters from the CorrectSpelling action are, typically:

- Parameter P4 is “Only regroup with “Heavy” Modalities”

- Parameter P5 is checked

- Parameter P6 is equal to 1

¶ Which “Similarity Measure” should I use?

There are 3 options for the “Similarity Measure”:

- Damereau-Levenstein

- Jora-Winkler

- Dice Coefficient

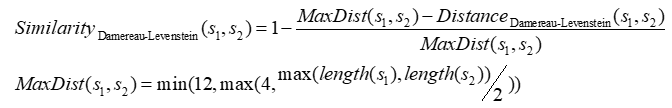

The “Damereau-Levenstein” similarity measure is derived from the “Damereau-Levenstein” distance between two strings. This distance is defined in the following way: The “Damereau-Levenstein” distance between 2 strings is the minimum number of operations needed to transform one string into the other, where an operation is defined as an insertion, deletion, or substitution of a single character, or a transposition of two adjacent characters.

We derive the “Damereau-Levenstein” similarity from the “Damereau-Levenstein” distance:

Here are some examples:

- The distance between “BRUSELS” (that we’ll define as the reference value) and “BRUSSSEL” is 3 because there are three errors:

- There are three “S” in the middle instead of one (2 insertions= 2 errors)

- The final “S” is missing.

- The distance between “BRUSELS” (once again, the reference value) and “BRUGELS” is 1 because there is only one error:

- The “S” letter is replaced by the “G” letter

Let’s look at the above two examples: The “Damereau-Levenstein” distance finds that “BRUGELS” is closer to “BRUSELS” than “BRUSSSEL”?? There is something very wrong about that. The example illustrates that the “Damereau-Levenstein” distance…

- …is worthless to compare strings when the distances between the strings might go above 1.

- …is ignoring the phonetic content of the characters. If you are interested in a phonetic encoding.

The Jaro-winkler similarity is an attempt to improve on the idea of the “Damereau-Levenstein” similarity. The Jaro-winkler similarity tries to stay meaningful in the case where the “Damereau-Levenstein” distance fails: i.e. when the distance between the strings might go above 1. Extensive tests demonstrates that, in practically all real-world studies, the Jaro-winkler similarity outperforms the “Damereau-Levenstein” similarity. The exact definition of the Jaro-winkler similarity is well documented on internet and will not be reproduced here.

NOTE :

The documentation about the “Jaro-winkler similarity” is available on Wikipedia on a page named “Jaro-winkler distance”. This is somewhat disturbing because it’s actually really a similarity measure (the higher the value, the closer the two strings are) and not a distance measure.

Although the Jaro-winkler similarity is better than the “Damereau-Levenstein” similarity, it’s still limited to “small” strings (for example: city names, surnames, etc.) where the number of differences between the compared strings stays relative small because of the small sizes of the strings (After all, the “Damereau-Levenstein” is just an improvement on the “Damereau-Levenstein” similarity and finally suffers from the same defaults). Thus, if you want to compute similarities between very long strings (such as “street names”, long “product names”, long “SKU names”, long “Book titles”, etc.), you’d better use the “Dice Coefficient” (the “Dice Coefficient” is also sometime named the “Pair letters similarity”).

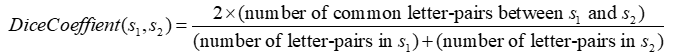

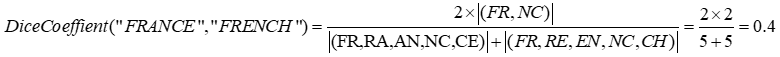

The “Dice Coefficient” is a similarity metric that rewards both common substrings and a common ordering of those substrings. The definition is:

The intention is that by considering adjacent characters (i.e. character-pairs), we take into account not only of the common characters, but also of the character ordering in the two strings, since each character pair contains a little information about the ordering. Here is an example:

Inside the ETL implementation of the Dice Coefficient, all the letter-pairs that contains a space character are discarded before any computation. This means that the similarity between the strings "vitamin B" and "vitamin C" is 100%. In this case (when you are interested in correcting small differences), you should rather use the “Damereau-Levenstein” or “Jaro Winkler” similarity.

¶ How to use the results?

The output of the CorrectSpelling action is a table that contains all the corrections to apply on the data to “clean it” completely. The easiest way to use this “Correction table” is the following pipeline: